- December 12, 2012Excerpts from biography: “Their two landrovers amusingly bore number plates commencing with the words BAN and BAD, perhaps not the…

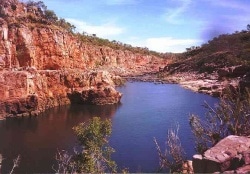

- September 14, 2012“Jedda” is the story of an Aboriginal girl caught between two cultures, and the tragic consequences. She has been raised…

- July 2, 2012The saga of making “Sons of Matthew” equalled the drama of the story itself. After reading Bernard O’Reilly’s books, “Cullenbenbong”…

- April 23, 2012RATS OF TOBRUK - 1944A story of Aussie heroism in the Tobruk chapter of World War 1, when men of…

- February 25, 2012There was a swashbuckling element of adventure behind the making of ‘Horsemen’, yet this film was a turning point in…